Martha

Martha Washington

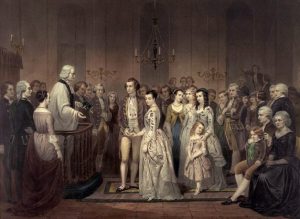

George Washington met Martha Dandridge Custis around March 1758. At the time, he was twenty-six, tall and handsome, with the reputation of a dashing military hero. She was twenty-seven, small and buxom, and one of the wealthiest women in all of Virginia. Her husband, Daniel Parke Custis, had died in July 1757, leaving her with a massive estate that consisted of thousands of acres and hundreds of slaves. She was also the mother of two children: John Parke (nicknamed Jacky) aged four and Martha Parke (nicknamed Patsy) aged two. Their courtship was brief; within months they were engaged and on January 6, 1759 they were married at her estate, ironically named the White House, in Williamsburg. Their wedding was a handsome affair, as George donned a blue and silver velvet suit with red trimmings and Martha wore a yellow gown and purple satin shoes. They honeymooned at the White House before settling down, finally, at Mount Vernon.

By all accounts, their marriage, which would last forty years until George’s death in 1799, developed into one of deep devotion. They both complimented each other in temperament. While he was stoic and serious, she was warm and affable. Together they were a rock-solid couple, both hardworking, down-to-earth and practical. George expressed his affection early in the marriage, stating “I am now, I believe, fixed at this seat with an agreeable consort for life and hope to find more happiness in retirement than I ever experienced amidst a wide and bustling world.” Of course, it didn’t hurt that they provided each other with security. George provided her with a dutiful and industrious breadwinner while Martha provided him the practical means of a large estate. The marriage lifted George Washington into the upper echelon of Virginia society as he became the guardian of one of the largest estates in the country.

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris’s portrait of George’s proposal

Their marriage endured the hardships of family tragedy and the demands of George’s career. However, they both submitted themselves to immense sacrifices and were conscientious in meeting their familial and social obligations. George remained devoutly faithful to Martha and adopted her two children, Jacky and Patsy, as his own. Martha proved to be an excellent hostess from the beginning of their marriage at Mount Vernon until forty years later during Washington’s years as president. She accompanied George throughout the Revolutionary War, spending about half the duration of the conflict with him. The sacrifice that both endured in the public service was reflected in a statement George made upon his retirement from the presidency: “Mrs. Washington and myself will do what I believe has not been done within the last twenty years by us – that is, to set down to dinner by ourselves.”

Many historians have speculated that George’s love for Martha reflected more of a deep friendship than one of fiery passions. There is evidence of his, when much later in George’s life, his letters to Martha came in the possession of a close friend Eliza Powell. She teased George that she might find some racy details in them, but George was assured that there was nothing of the sort, perhaps reflective of a marriage where the passions had settled. Additionally, George later wrote to his adopted granddaughter Nelly Custis on his practical views of romance, stating “love may and therefore ought to be under the guidance of reason, for although we cannot avoid first impressions, we may assuredly place them under guard.”

Martha appears to have been a beloved figure throughout her life. Washington’s troops affectionately referred to her as “Lady Washington.” During the war, she worked hard to comfort the sick soldiers, knitting socks, patching garments, and making shirts for. Abigail Adams later described Martha as “one of those unassuming characters which create love and esteem. A most becoming pleasantness sits upon her countenance and an unaffected deportment which renders her the object of veneration and respect.”

Sadly for historians, Martha burned all of their correspondence after his death. However, two letters survive. One of them reveals George’s abiding love and affection for Martha. Soon after his selection as commander of the Continental Army, he touchingly wrote to her, “I retain an unalterable affection for you which neither time or distance can change.” His death in 1799 left her bereft and she died a mere two years later in 1802.

Print of George and Martha’s wedding

.

Father Figure

Jacky Custis, Source: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Although Washington, the “Father of His Country,” famously had no children of his own, he acted as a surrogate father to Martha’s two children, Jacky and Patsy, and provided munificently to many of his nephews and nieces, paying for much of their education expenses. Additionally, many of them were invited to live at Mount Vernon, as if to make up for the Washingtons’ own inability to sire children.

Washington, cognizant of his own lack of education, provided his adopted children with a Scottish tutor in 1761. He was determined to provide them with the education that he, himself, had missed out on. Unfortunately, Jacky was an idle and apathetic youth. Washington sent him to private school in Fredericksburg and to King’s College (later Columbia University) in New York but both times Jacky wasted his opportunities in drunken debauchery. In 1773, Jacky rushed into marriage with a young woman named Eleanor Calvert. The proposal had occurred without Washington’s knowledge or approval, much to his consternation.

Patsy Custis, Source: Tudor Place Foundation

While Washington lamented Jacky’s dissipation, he and Martha doted over Patsy. Their affection for her was magnified by her tragic condition of epilepsy. She began suffering from seizures at the age of twelve in 1768. Soon, the seizures would occur more frequently and severely, with no discernible cure. George and Martha, despite applying a number of the remedies of the day, could only watch helplessly and lived with the constant fear for Patsy’s life. On June 19, 1773, Patsy died, leaving George and Martha grief-stricken. It was written that he “solemnly recited the prayers for the dying while tears rolled down his cheeks and his voice was often broken by sobs.”

Despite Jacky’s lassitude, he managed to serve in the Virginia House of Delegates and raise four children, Elizabeth Parke, Martha Parke, Eleanor Parke, and George Washington Parke Custis. Despite their difficult relationship, Jackie volunteered as an aide for his stepfather as he was orchestrating the siege at Yorktown. Tragically, Jacky caught camp fever at Yorktown, dying at the age of twenty-six in November 1781. It was another tragic blow for the Washingtons, coming right on the heels of great military triumph.

Nelly Custis

After Jacky’s death, his daughters Elizabeth and Martha lived with his widow. The youngest two, Eleanor and George, known as “Nelly” and “Washy,” were adopted by George and Martha Washington as surrogate children. The two children were at a tender age: Washy was two and Nelly was seven months old. Theirs was a happy childhood at Mount Vernon, showered with love and affection from their adoptive parents. Washy, however, inherited many of his father Jacky’s listless traits, idling his time away and unfocused on his studies. Again, this would prove a frustrating situation for Washington. By contrast, George and Martha doted over Nelly, who grew to be a beautiful and vivacious young brunette. She was talented as an artist, a musician (she played the harpsichord), and a dancer. She also had a propensity for mischief and constantly spurned many-a-suitor. One admirer wrote that she “has more perfection of form of expression, of color, of softness, and of firmness of mind that I have ever seen before.”

Washy Custis, in his old age

In 1789, when Washy was ten and Nelly was eight, they joined President Washington at his mansion in New York. Later, they followed the President to Philadelphia for the bulk of his time in office. There, Washy attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), but later dropped out and attended St. John’s College in Annapolis. Nelly grew up in the high political society of the nation’s capital, serving as hostess at the executive residence. After the presidency, Nelly fell in love with Washington’s nephew, Lawrence Lewis (son of Washington’s late sister Betty), and they married at Mount Vernon on February 22, 1799, her adopted father’s sixty-seventh birthday. Washington attended the wedding in his Revolutionary War uniform.

After Washington’s death, Washy would have a successful career as an orator and playwright. In 1804, he married Mary Lee Fitzhugh and have four children, only one of which would live maturity. That child, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, would marry General Robert E. Lee, the future Confederate general. Washy died October 10, 1857, just a few years before the beginning of the Civil War.

During his life, Washington loved Nelly as if she were his own daughter and was constantly charmed by her buoyant personality. To her he dispensed fatherly advice on virtue and domestic happiness. Nelly and Lawrence had eight children, but only three of which would live to maturity. Nelly forever considered herself a preserver and heir of George Washington’s legacy, reminiscing about her famous grandfather, confirming or debunking various myths and legends. Late in Washington’s life, Nelly wrote to him “with grateful affection” for his role “as a parent to myself and family.” Nelly died in July 1852 at the age of seventy-three.

President and Mrs. Washington, with Washy and Nelly